Calligraphy: A Collector's Apologia

"Had I been born Chinese, I would have been a

calligrapher, not a painter," Picasso once said.1

Without knowing any Chinese, Picasso nonetheless

recognized an artistic expressiveness in Chinese

script that characterizes this classic art form.

Seldom has the written word assumed such an

importance in a culture. With no real history of

public oratory comparable to the Greco-Roman

tradition in the west, written (or more precisely

brushed) Chinese was the primary mode of

communication.2  While

advertising is ubiquitous, a walk down almost any

street in any Chinatown reveals a bewildering array

of signage that underscores this trait of Chinese

culture. The eye is the privileged sense organ, not

so much the ear. Gordon Barrass notes that it is no

accident that Chinese calligraphers often supplement

their living by creating signs for shops or public

institutions such as museums and parks.3

Mao Zedong and other leaders in the new China, many

of whom were quite passionate about calligraphy,

penned a number of such public placards for various

schools and public spaces in Beijing.4

This was yet another mark of an imperial tradition in

which a ruler's calligraphy on public display

conveyed meanings beyond the mere words inscribed on

a plaque.

While

advertising is ubiquitous, a walk down almost any

street in any Chinatown reveals a bewildering array

of signage that underscores this trait of Chinese

culture. The eye is the privileged sense organ, not

so much the ear. Gordon Barrass notes that it is no

accident that Chinese calligraphers often supplement

their living by creating signs for shops or public

institutions such as museums and parks.3

Mao Zedong and other leaders in the new China, many

of whom were quite passionate about calligraphy,

penned a number of such public placards for various

schools and public spaces in Beijing.4

This was yet another mark of an imperial tradition in

which a ruler's calligraphy on public display

conveyed meanings beyond the mere words inscribed on

a plaque.  Mao even created

the banner for the People's Daily, thus putting his

calligraphy on daily display (see picture to the

left). Why is it that such an importance is given to

writing that goes beyond merely a clear presentation

of ideas?

Mao even created

the banner for the People's Daily, thus putting his

calligraphy on daily display (see picture to the

left). Why is it that such an importance is given to

writing that goes beyond merely a clear presentation

of ideas?

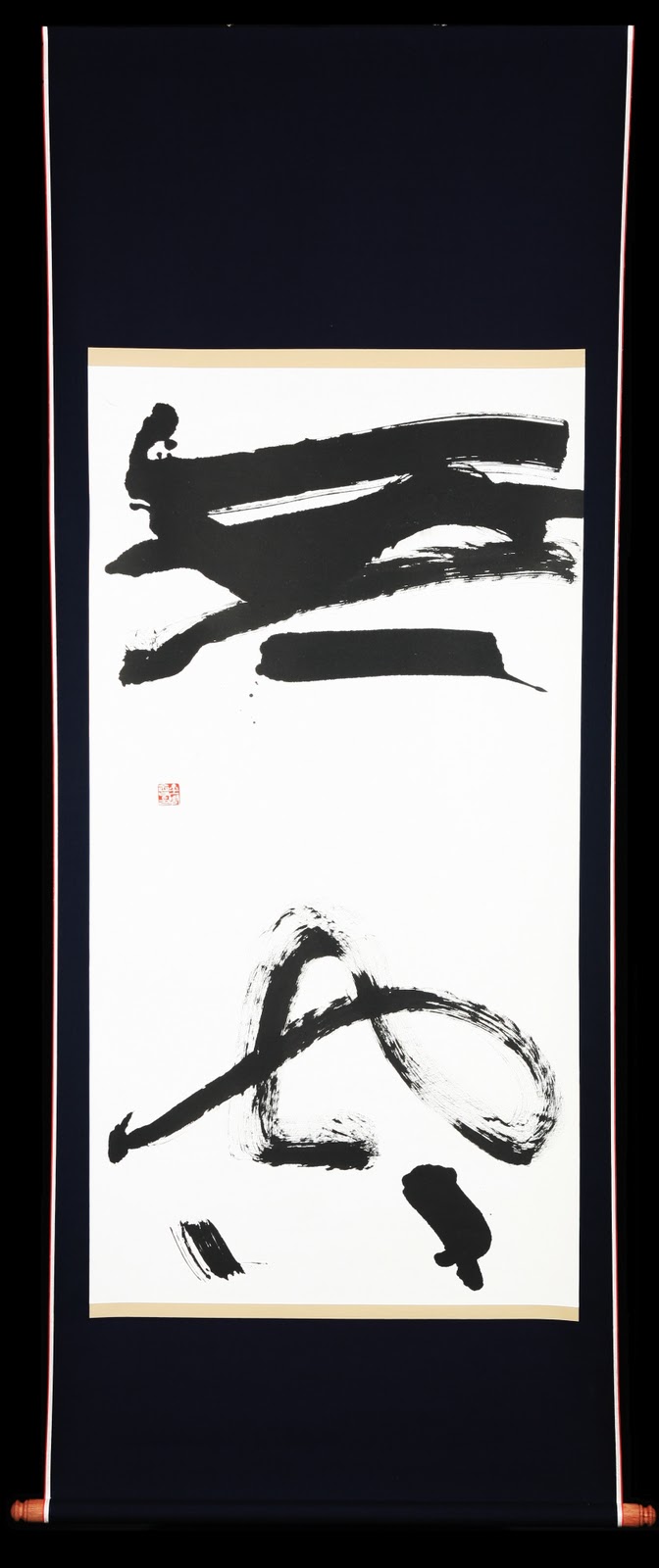

Calligraphy brings to words or characters a dimension other than simply meaning—namely, gesture. Calligraphy is in essence performance art with a residual shadow. It captures the skills and emotions of the writer at a point in time and freezes it in a work that may be viewed over and over. The swirls and strokes of the brush, the flow of ink-now heavy and wet, now dry and streaky--the very absorbency of the paper on which the ink diffuses or pools, all capture a specific moment in time. The calligrapher's tracings on paper, his or her gesture, as they write a character become a visual map. The eye can perceive the flow of the brushwork as clearly as it can follow dancers' movements as they shift from step to step, stance to stance.

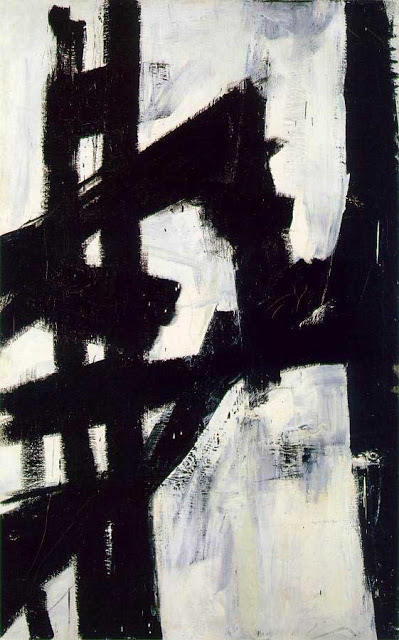

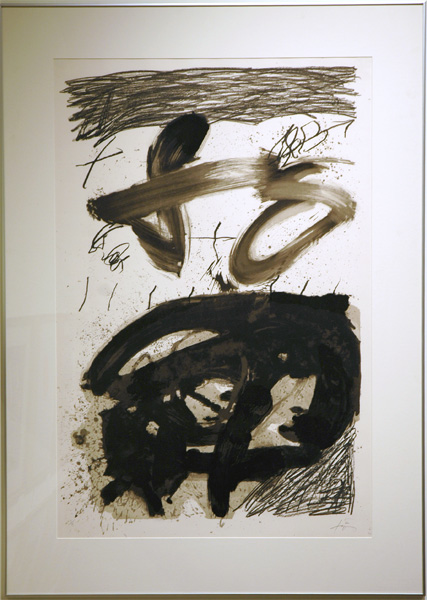

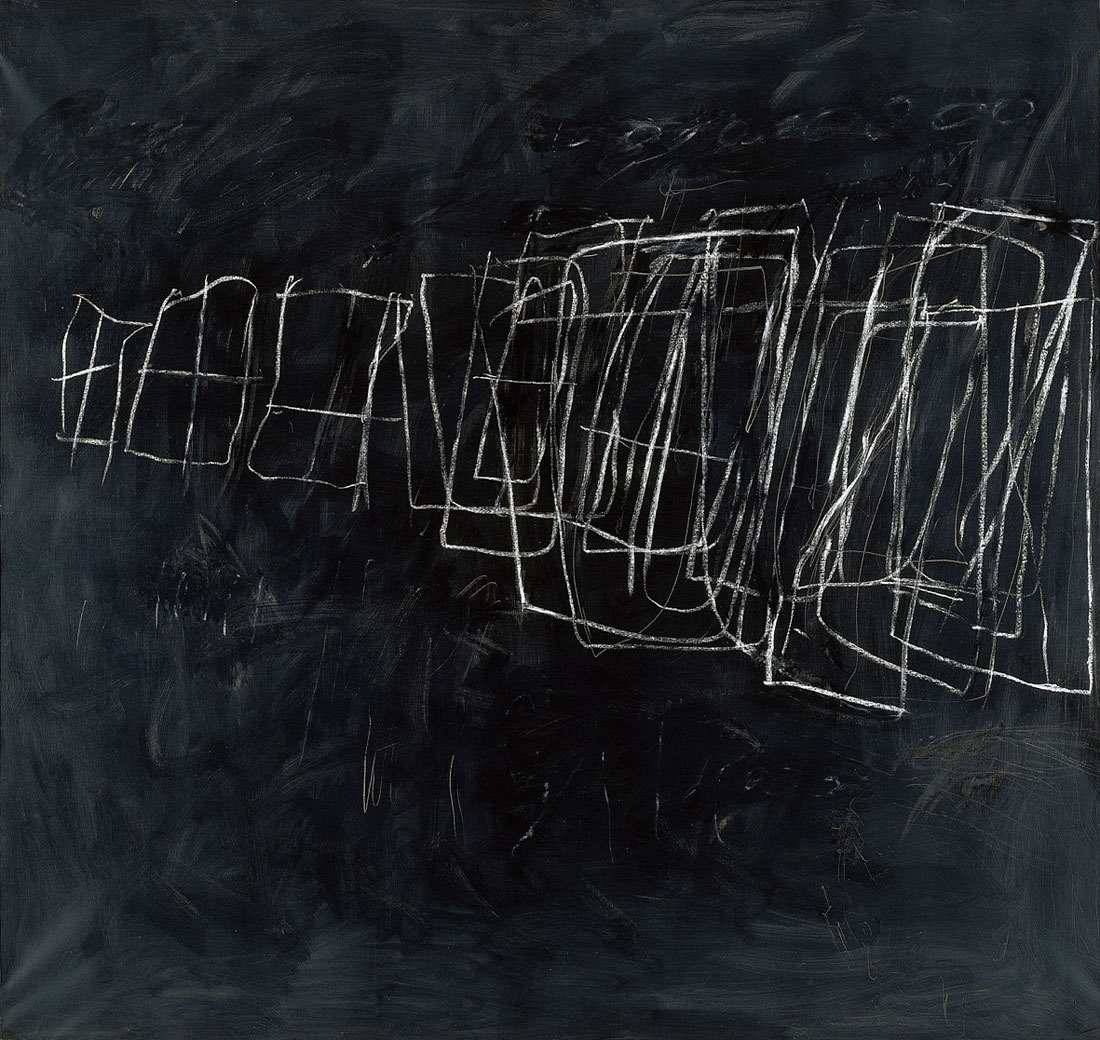

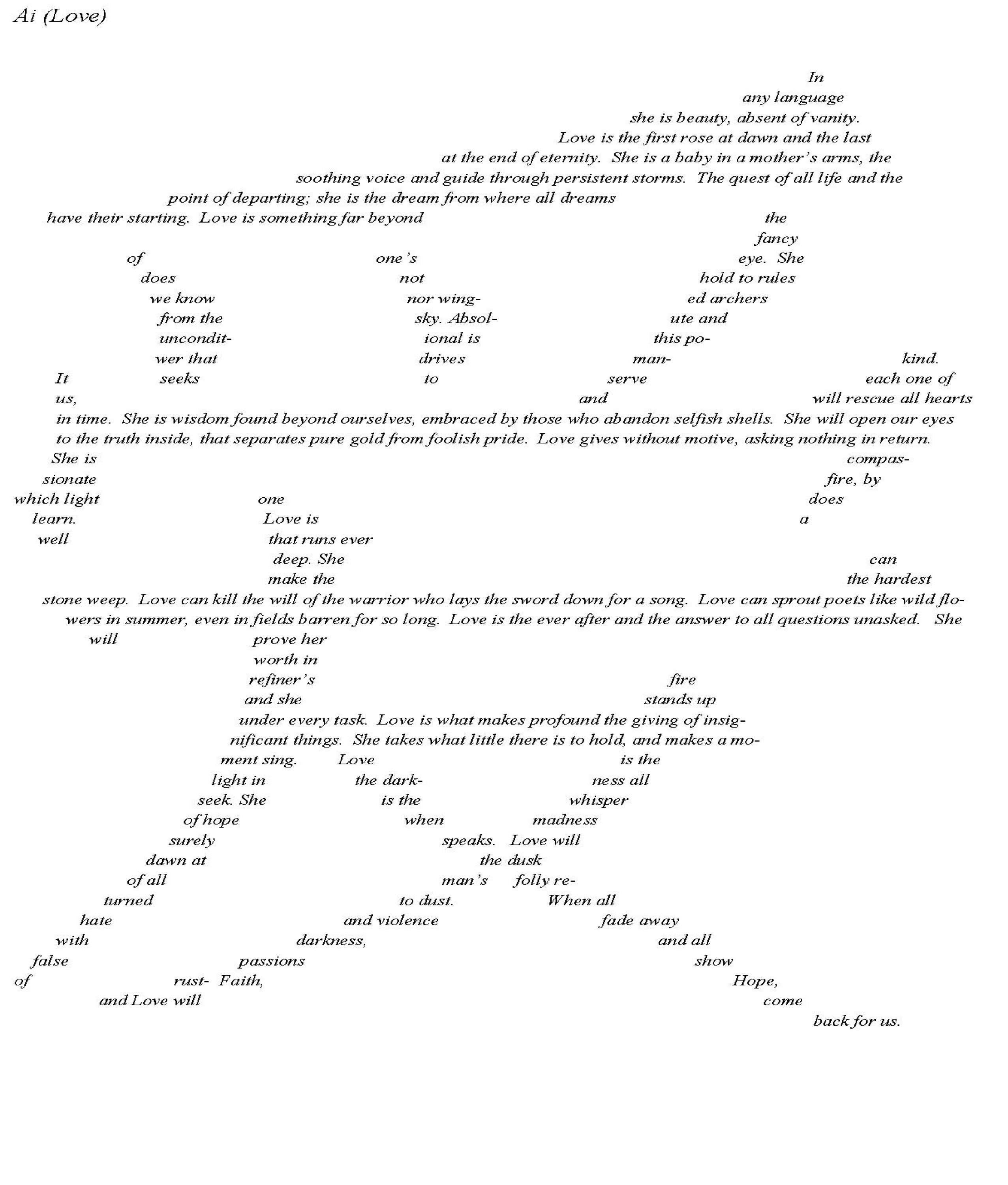

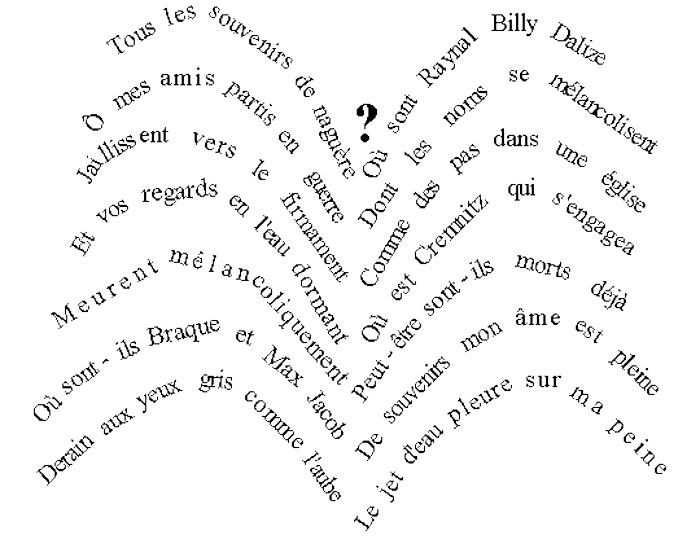

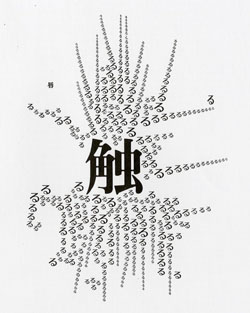

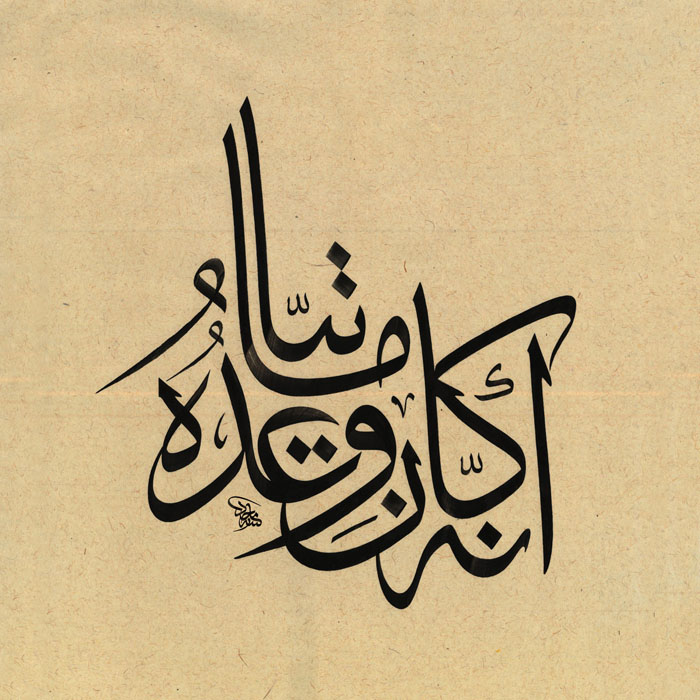

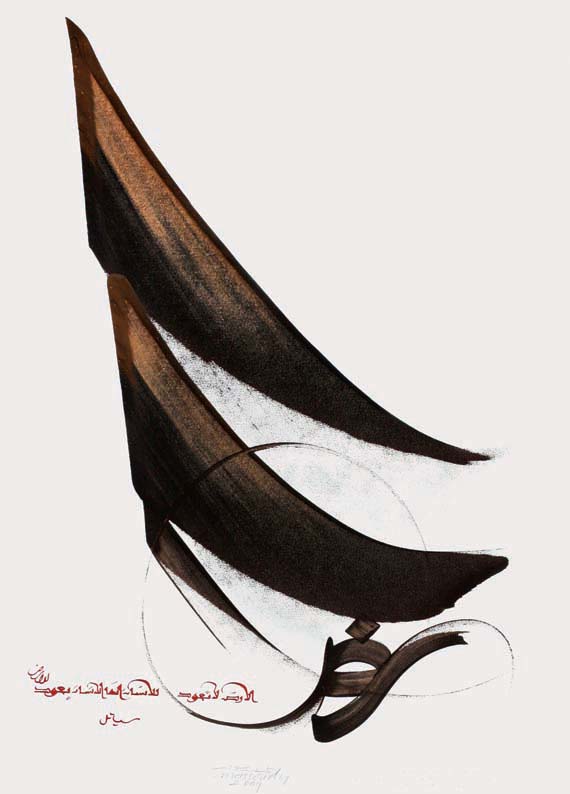

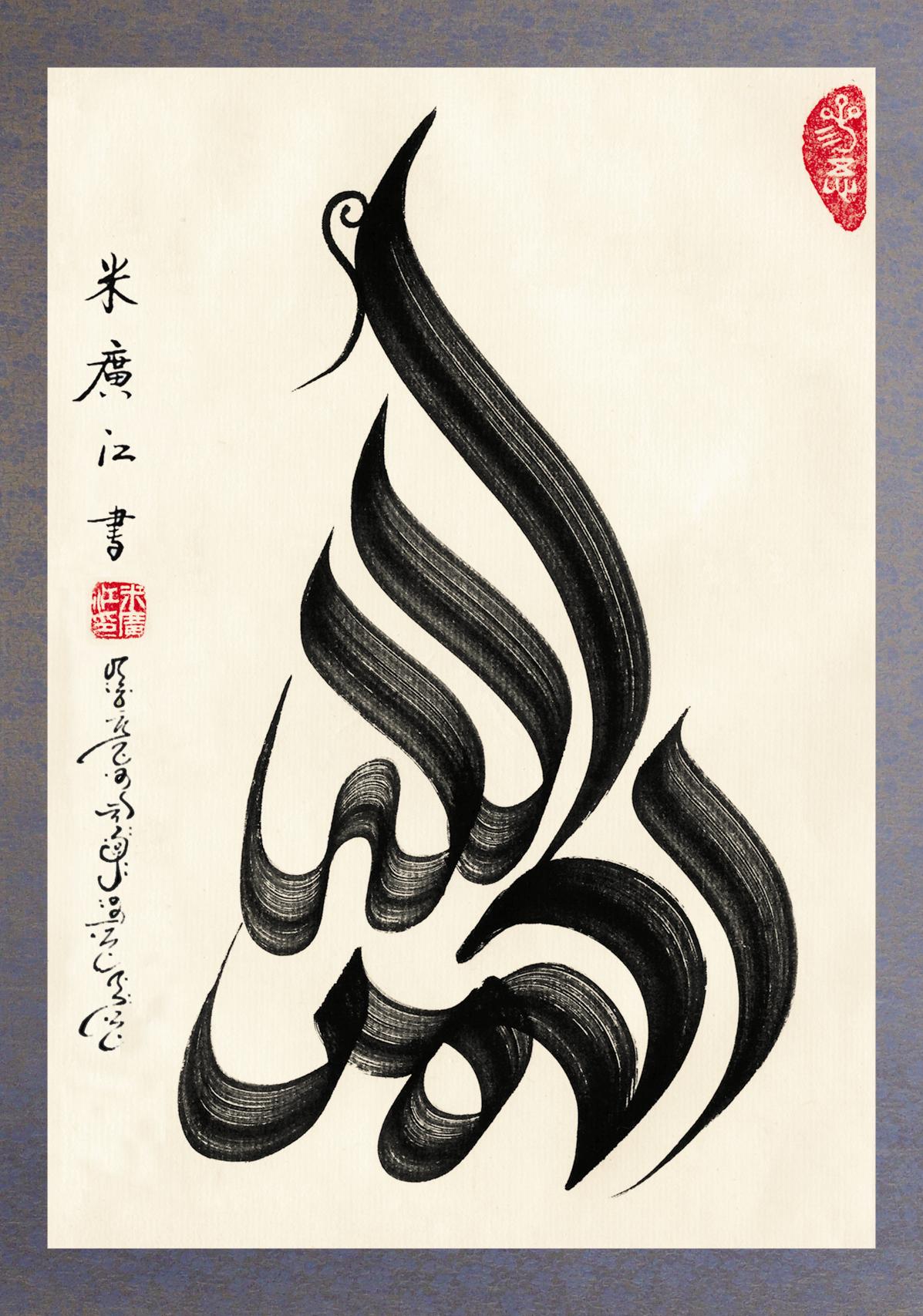

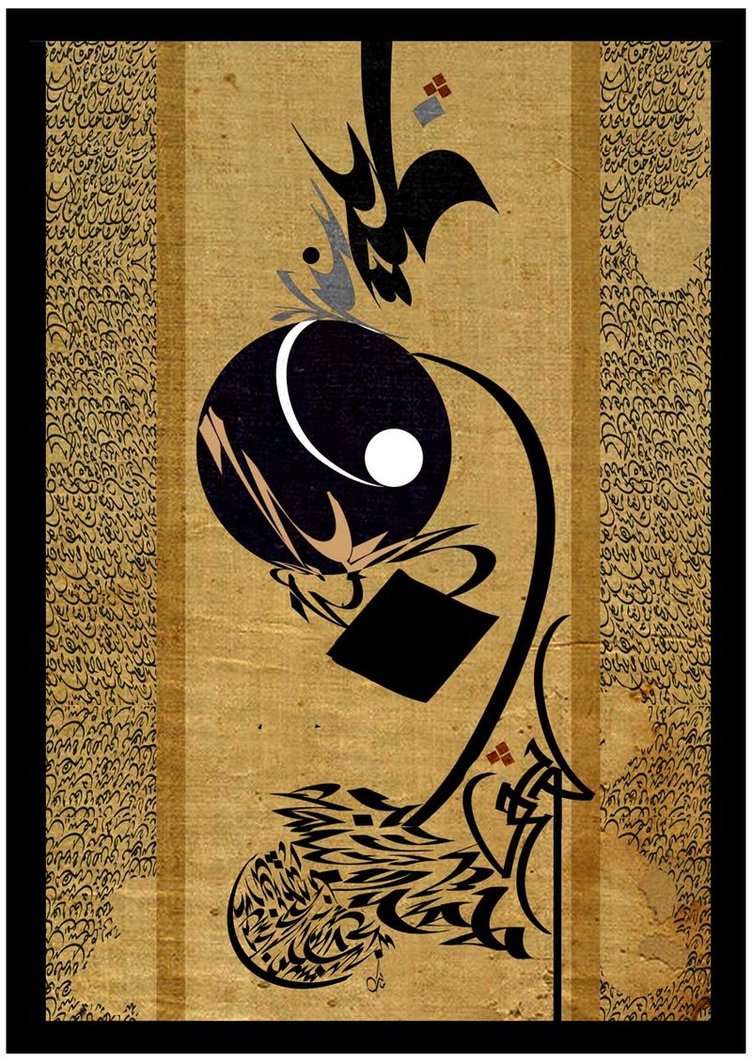

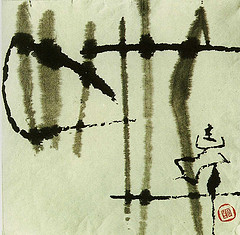

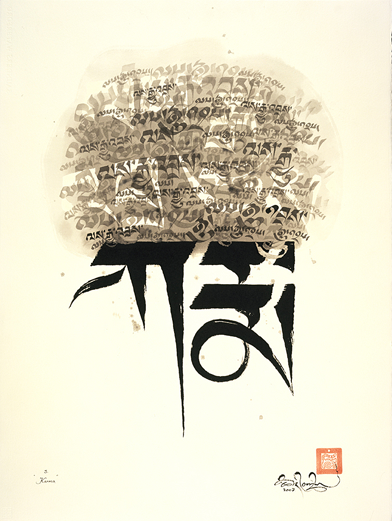

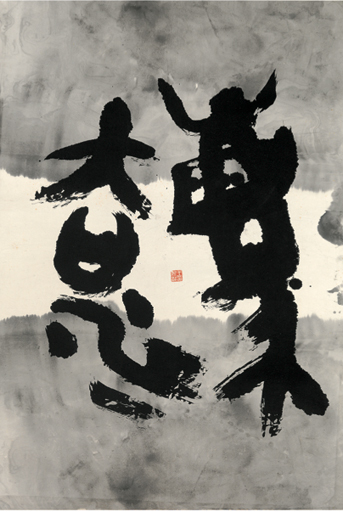

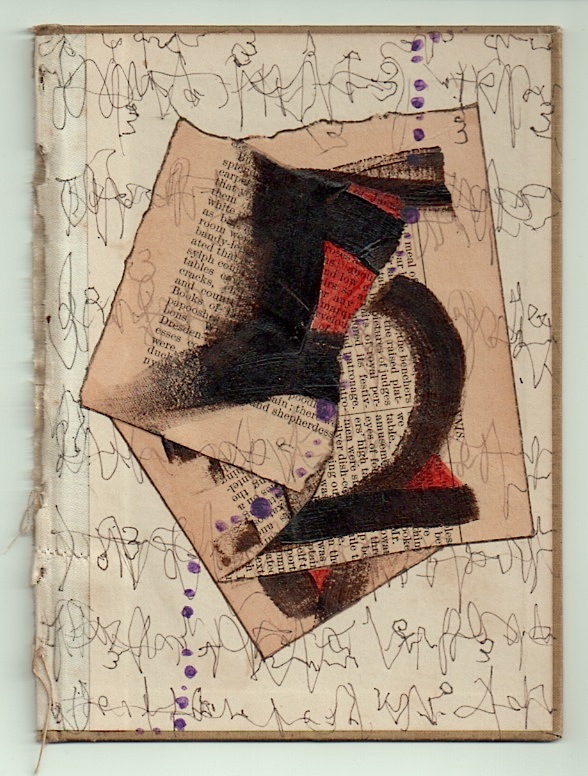

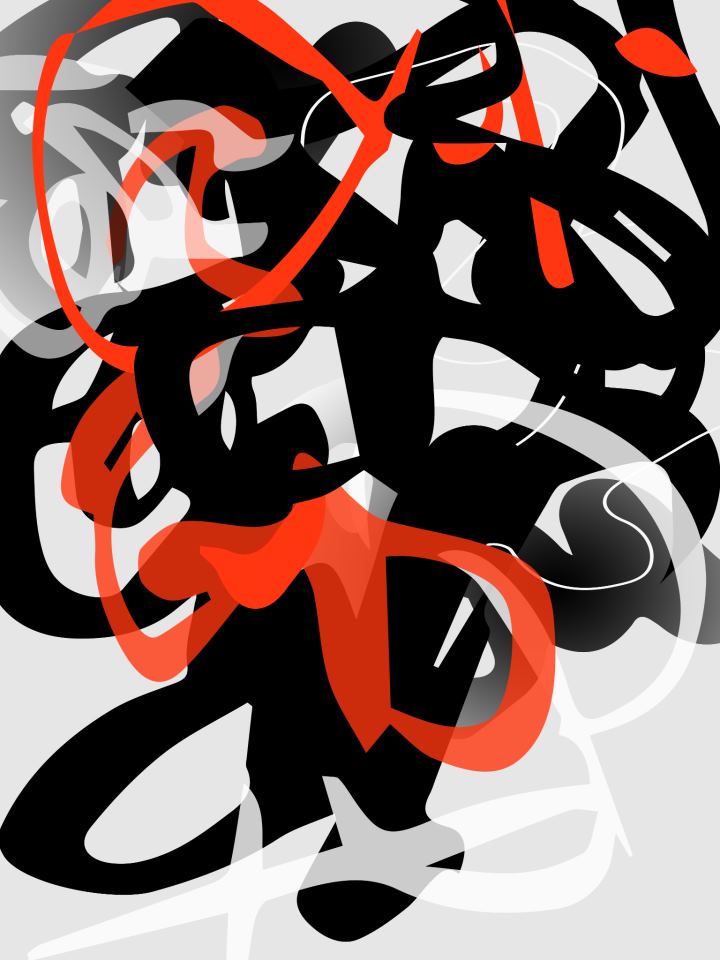

When I think of calligraphy in the largest sense, all manner of artists with a "calligraphic" component to their work come to mind. These can range from abstract expressionists to visual poetry (aka concrete poetry) to asemic writings (aka abstract calligraphy).They all share a concern for shape, composition, and gesture—with or without any inherent meaning. The brushwork may be with paint rather than ink, canvas rather than paper, but nonetheless it captures, sometimes rather strongly, the brush touching a surface. Another art form is visual poetry which arranges the elements of script (letters, words, type face, handwriting, etc.) to form shapes that compliment or add further visual meaning to the poem. Even two very differnt calligraphic tradions can combine to form paintings of fresh impact. See, for example, the works of Haji Noor Deen Mi Guang Jiang which use the Sini script that fuses Arabic and Chinese styles. The Chinese artists Xu Bing and Gu Wenda have even gone so far as to create "new Chinese characters" that mean absolutely nothing. Xu Bing has also invented his New English Calligraphy which presents English words and letters reworked to appear as Chinese script.5 Others such as Takahiro Tomatsu and Gu Wenda use unconventional tools and/or media—Takahiro uses fistfuls of the hair on his head as a brush and Gu Wenda incorporates human hair into some of his works.

| Abstract Expresionism |

Franz Kline |

Pierre Soulages |

Antoni Tàpies |

Cy Twombly |

Robert Motherwell |

| Visual Poetry |

John Ecko |

Antonia Valero |

Guillaume Appolinaire |

Niikuni Seiichi |

Win Leowarin |

| Modern Islamic Calligraphy |

Ruh Al-Alam |

Majid al-Yousef |

Hassan Massoudy |

Haji Noor Deen Mi Guang Jiang |  Malik Anas Al-Rajab |

| Modern Eastern Calligraphy |

Gu Gan |

May Shoko Kanazawa |

Kim Jue Whe |

Tashi Mannox |

Wang Donling |

| Asemic Writing |

Yorda Yuan |

Lanny Quarles |

Nancy Bell Scott |

Meeah Williams |

Harkim Chan |

Jiuan Heng in his essay

"Calligraphy" references Zhang Huaiguan's distinction

between 字 [zi4], the character as

transcribed, and 书 [shu1], the act of

writing.6 The character itself is written

in a prescribed way with strokes made in a determined

order, and the whole is balanced within an imagined

grid to achieve regularity of stokes and spacing.

Each character's size is consistent with the others

and thus produces a uniform text. But in the act of

writing personality, training and talent can

transform the shape of a character into a lively

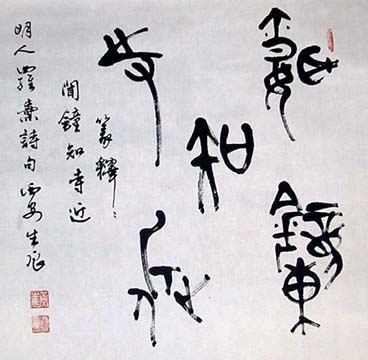

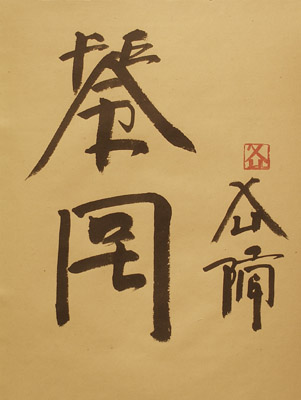

entity with its own life and spirit.  Penmanship is not calligraphy. Gesture turns mere

script into calligraphy; i.e., something of interest

in its own right quite apart from the character's

inherent meaning. The traditional vertical lines that

structure Chinese texts may bend or sway or change

shape altogether as a newer, fresher kind of

composition results from the way the characters are

grouped on a page. In the example to the right, the

phrase 闻 钟 知 寺 近

(the sound of bells lets one know they are nearing

the temple) appears in jin wen script on the

right side in a cluster of characters while the

writing on the left preserves the traditional pattern

of vertical movement. Part of the pleasure in this

example arises from this contrast that the eye

perceives. In both parts the meaning is understood by

reading from top to bottom, right to left, but the

composition of larger characters irregularly grouped

and the smaller ones in straight lines achieves a new

balance that just seems right, even natural, on the

paper. The eye is satisfied by this formal element

even without knowing the text's sense. In this

respect, calligraphy is rather like some abstract art

where the formal elements of color, line, and

composition are the meaning not a representation of

any thing in particular. This pleasure is—at

least partly—independent of text and history.

Knowing what the text means and also the knowledge

that the script on the right is jin wen, a

very early form of Chinese writing, adds yet other

layers of appreciation, but they are not the only

meaning to be discovered in this composition.

Penmanship is not calligraphy. Gesture turns mere

script into calligraphy; i.e., something of interest

in its own right quite apart from the character's

inherent meaning. The traditional vertical lines that

structure Chinese texts may bend or sway or change

shape altogether as a newer, fresher kind of

composition results from the way the characters are

grouped on a page. In the example to the right, the

phrase 闻 钟 知 寺 近

(the sound of bells lets one know they are nearing

the temple) appears in jin wen script on the

right side in a cluster of characters while the

writing on the left preserves the traditional pattern

of vertical movement. Part of the pleasure in this

example arises from this contrast that the eye

perceives. In both parts the meaning is understood by

reading from top to bottom, right to left, but the

composition of larger characters irregularly grouped

and the smaller ones in straight lines achieves a new

balance that just seems right, even natural, on the

paper. The eye is satisfied by this formal element

even without knowing the text's sense. In this

respect, calligraphy is rather like some abstract art

where the formal elements of color, line, and

composition are the meaning not a representation of

any thing in particular. This pleasure is—at

least partly—independent of text and history.

Knowing what the text means and also the knowledge

that the script on the right is jin wen, a

very early form of Chinese writing, adds yet other

layers of appreciation, but they are not the only

meaning to be discovered in this composition.

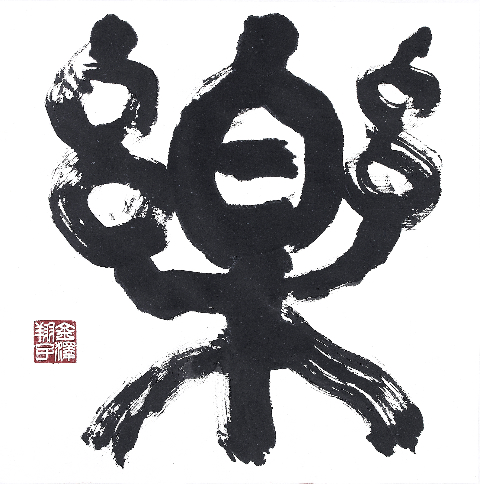

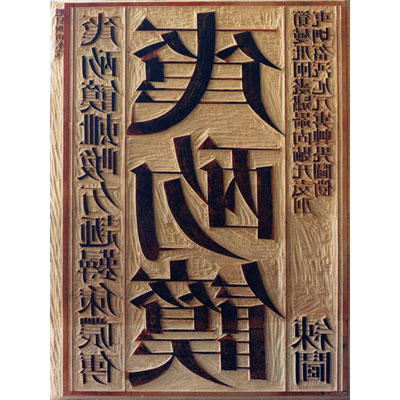

Compare the two renditions of the same character

below.  Both are legible and

communicate a meaning. However, the character on the

right has vital and dynamic lines,while the one on

the left seems stiff and wooden. The meaning is clear

in both cases—the character 福

(fu2 good fortune, good luck). But the one on

the right seems like a blessing, it bursts onto the

eye forcefully, just as we might wish good luck to

enter our lives powerfully. This serves as an example

of how gesture—the very act of

writing—can transform a character into art. A

good piece of calligraphy is like a living, breathing

body. It coordinates blood, flesh, muscle, bone and

spirit into an organic whole. The contrast could not

be plainer even if you do not know what the character

means.

Both are legible and

communicate a meaning. However, the character on the

right has vital and dynamic lines,while the one on

the left seems stiff and wooden. The meaning is clear

in both cases—the character 福

(fu2 good fortune, good luck). But the one on

the right seems like a blessing, it bursts onto the

eye forcefully, just as we might wish good luck to

enter our lives powerfully. This serves as an example

of how gesture—the very act of

writing—can transform a character into art. A

good piece of calligraphy is like a living, breathing

body. It coordinates blood, flesh, muscle, bone and

spirit into an organic whole. The contrast could not

be plainer even if you do not know what the character

means.

Zhang Yiguo got it right I believe when he observed that: "Now I am confident that even though people do not understand the language of the characters, nevertheless they do understand the language of art, that is, the quality of line: brushwork, construction, application of ink, rhythm and composition."7 Whatever the tools, whatever the medium, the interplay of interesting writing and some artistic vision forms my personal pleasure in this art form.

- Barrass, Gordon S. The Art of Calligraphy in Modern China. p. 54. Picasso said something similar about Arabic calligraohy: "If I had known there was such a thing as Islamic Calligraphy, I would never have started to paint. I have strived to reach the highest levels of artistic mastery, but I found that Islamic Calligraphy was there ages before I was." Quoted in The Aura of Alif (Prestel Publishing, 2010) by Jürgen Wasim Frembgen. See also Gertrude Stein's Picasso (London: Batsford, 1938), p 37 ff. where she discusses the role of calligraphy in Picasso's work.

- Op. cit. p. 17.

- Op. cit., pp. 108 ff.

- Op. cit., pp.41-42.

- See below an example of "fake" Chinese from Xu Bing's Book of Heaven and an example of his New English Calligraphy:

In both cases the script looks like Chinese except that the characters in his Book of Heaven work have no meaning while in Fear Not you can see the English words once you get past the initial reaction that these are Chinese characters. Notice that his signature is also in this script.

Xu Bing

Book of Heaven

Xu Bing

Fear Not - Heng, Jiuan, "Calligraphy" in Encyclopedia of Chinese Philosophy. (New York: Routledge, 2003). p. 25.

- Zhang Yiguo. Quoted in an interview by Yang Yingshi in the China Daily (01/02/2003). See also Leah Daniel. "Morita Shiryu and Artistic Classification: Avant-Garde, Abstract Expressionist, or Sho?" and "A History of Chinese Calligraphy – Postmodernism: The Avant Garde Movement – A Globalized Calligraphy".

For selections from my collection see: Chinese Calligraphy | Japanese Calligraphy

Art Collections | Buddhism | Contact | Haiga | Home | Site Map | Updates